Pages 74-78

by Kamil Ibrahimov

Relations between India and Azerbaijan extend back to ancient times; however they were particularly strong in the Middle Ages. Historically, the celebration of Baku as the city of “sacred fires” was a significant feature of Indian-Azerbaijani relations. It is known that Azerbaijan practised fire-worship and Christianity before the Arab invasion and there were many religious centres or shrines. One of the main centres of fire-worship was ancient Baku. It is widely known that in the early Middle Ages, Baku was already being mentioned as the location of eternal fires. The first such reference was made by a Byzantine author of the 5th century. This information surely refers to Baku’s eternal flames, to the sea shore and, it seems, to the fires at Surakhani and on Pirallahi Island. Writers in the Middle Ages and later mentioned the displays of combustible gas on the Absheron Peninsula – on Pirallahi Island, in Surakhani village, in Baku Bay and on Shubani Mountain. The strongest gas vents were in Surakhani village. Atesh-I Bagavan was mentioned by Gevond in the 8th century as Ateshi-Baguan, which means “fires of Bagavan”, “fires of the city of God” and which was located in the area around Baku. Absheron, bursting with oil and streams of combustible gas, was also included in the province of Paytakaran. The name Ateshi-Bagavan may have been connected with the sanctuaries and ancient temples of fire-worshippers, which existed in the Baku area or on Absheron in ancient times.

Archaeological evidence.

Trading relations clearly existed between Azerbaijan and India in ancient times, many centuries before Christ. Various findings of cowrie shells and other archaeological information testify to this. Cowries have been found in great quantities at burial sites in the settlements (Mingachevir) and cities of Azerbaijan and they are believed to originate in the Bronze Age (end of the second, beginning of the first millennium B.C.) The cowrie, as is known, is abundant in the Indian and Pacific oceans, and its use as coinage can be traced in India and neighbouring countries from the furthest past. In the process of barter trade, these shells served as common currency, through which barter was conducted.

Cowries, widely used in Azerbaijan, appeared here from India by sea, via Iran. They served as amulets, talismans etc. Ancient writers claim that there was a water way from the borders of Iran to upstream of the Rioni River, through the Black Sea and the navigable rivers of Central Asia, through the Caspian Sea, to the Kur River and Caucasian Albania.

English merchants bought cowries in India and, later, sold them in Guinea for twice or three times the price. There were very extensive trading operations in Central and Western Africa at that time, and they were transacted using cowrie shells.

Let’s take a look at some of the archaeological information testifying to the cult of fire and the expansion of fire-worship in Azerbaijan. An arched monument discovered in Icheri Sheher (Baku’s Old City) in 1964, is the yard of a mosque, cleared in 1989, near Maiden Tower. The mosque is a monument from the tenth century. An octagonal and triple-stepped pedestal, made of stone, and an octagonal column were discovered by the archaeologist O.S.Ismizadeh in the yard of the ancient temple. This construction was not destroyed during the construction of the mosque, and has survived to our time. The repetition of octagonal motifs is of great interest. The column at the centre of the monument seems to have served as a torch-holder during religious ceremonies.

The triple-stepped and octagonal pedestal, the octagonal column and other signs of antiquity prove once more that Baku was already inhabited in those ancient times. The fact that the city was inhabited by fire-worshippers is not in the slightest doubt.

Three metallic bronze cast items were discovered within the grounds of the Shirvanshahs’ Palace in Baku during archaeological excavations; they were in layers of sand, 2.4 metres below the modern surface. One of them is a wide, shallow, open cup on a stand (height 8.8 cm) with its outer surface decorated with borders. The two other items are lamps: one 12.9 cm high, the other 10.7 cm. These items have an ancient appearance. “The position in which they were discovered (laid next to each other in a layer of clear sand) indicates that they had probably been hidden”. Their shapes are similar to those in a picture on a signet ring from Mingachevir and refer to a pre-Islamic period; we may assume that they are connected to the cult of fire and fire-worship. The Arabs followed the Zoroastrians and people of other faiths, and impressed Islam upon those who resisted.

As we know, fire-worship was prevalent in the second half of the first millennium in Absheron and Christianity was widespread in the early Middle Ages in Shirvan, Mughan, Lenkeran, the Talysh region, South Azerbaijan and in the north of Azerbaijan. In several regions the most ancient cults have been preserved – the cults of rock, wood, moon and sun worship etc.

The Indian “Multana” caravanserai.

In the 15th century, a colony of Indian merchants lived and had caravanserais in Baku, Shemakha, Tabriz and other Azerbaijani cities. The 15th century Indian Multana caravanserai still stands in the ancient fortress of Baku – Icheri Sheher. Trading by Indian merchants, who mainly bought raw silk produced in Shirvan, Shemakha and other places, continued in Azerbaijan until the 16th century and later.

About 50 m north-west of the Baku temple, Maiden Tower, there is a caravanserai building – totally reconstructed in the 14th century on the foundations of a more ancient construction - which had obviously served the same purpose. This building still carries its ancient name – the “Multana” caravanserai, taking the name of an Indian tribe of fire-worshippers. It seems that the name was given to the caravanserai in the 15th century, inherited from its more ancient predecessor, built in times of rigorous Zoroastrianism - the Sassanid era, or even earlier; it is hard to imagine that any building could have been given a pagan name while Islam held sway. This caravanserai was restored again in the 17th century and the last major work carried out on it was a reconstruction from 1974-1976.

Constructed right next to the high stone wall surrounding the temple, not far from the main gates, which were located a little further west, the Multana caravanserai served as a shelter for Zoroastrian pilgrims from far India. The Indian pilgrims often came to the ancient city of Ateshi-Baguan and stayed at their caravanserai to participate in worship and sacrificial offerings at the principal temple of the Mazdaites - and later the Zoroastrians - the Baku temple of seven-headed fires.

The temples of Baku were clearly visited by followers of the Zoroastrian religion. Opposite the caravanserai for Indian fire-worshippers was the Bukhara caravanserai for merchants from Central Asia. The latter had been reconstructed in the 15th century on the site of an older building which had probably been a shelter for fire-worshippers from Sogda, Khorezm and Bactria. It would seem that these caravanserais enabled merchants from distant countries to combine business with worship of their God in the cult complex. While the flames continued to burn in the Baku, the temple complex of the ancient city of Ateshi-Baguan was probably the main cult centre of Mazdaism and Zoroastrianism, popular across Caspiana, Albania and Midia – Atropatena,

Baku Juma – Cathedral Mosque.

It is no coincidence that some people in Baku still believe that the Juma Mosque, located within Baku’s Old City walls, was built on the site of an ancient fire-worshippers’ temple. A traveller, who saw the Baku Juma Mosque in 1873, described four arches in the middle of the mosque; their tops did not overlap. Those arches were ancient shrines; they had been preserved from the ancient temple of fire-worshippers and reconstructed into a Muslim mosque. Thus, the temple was open on all four sides and topped by a cupola. In the middle there was a hole/well, where fire – combustible gas - burned continuously. A writer who visited the Juma Mosque in 1887 compared it to the fire temple in Surakhani.

Ateshgah.

One of the most interesting and peculiar historical monuments near Baku is the fire temple of Indian fire-worshippers, called Ateshgah. It is located on a flat area not far from the sea, to the south-east of the village of Surakhani on the Absheron Peninsula; it is currently surrounded by oil fields on all sides. The cells and the temple were constructed at different times between the 17th and 19th centuries. The cells were enclosed within a surrounding wall at the end of the 18th century. Ateshgah was constructed by Indians living in Baku, the majority of whom came from Northern India and were members of the Sikh community.

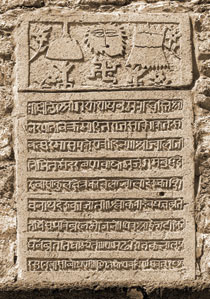

All the buildings, reminiscent of a caravanserai, are designed as a closed pentagon and consist of 24 cells and rooms, which used to accommodate visiting pilgrims. The entrance is two-storeyed; on the second floor is a room with two windows and a door between them in the northern and southern walls and a door in the short eastern and western walls. This place for visiting guests was called the “balahane”. There is a stone staircase from the balahane into the internal yard. On the outer wall of this room there is some Indian writing. There is more Indian writing on the ground floor above the entrance door. On the four corners of the flat roof of the balahane there are four stone pipes, where fire used to burn. Inside the yard, enclosed within a walled pentagon, is the temple-shrine in the form of a rotunda, in the middle of which there was a well, where the gas (methane) flamed; it also burned above the cupola at the four corners of the building. The shrine itself is a four-sided construction, open on all sides, which means it consists of four rectangular columns, joined by arches and topped by a cupola. The walls of the shrine are covered by finely-shaped medium-size limestone plates. On the northern wall of the shrine, facing the balahane, there is some Indian writing above the arch. The inner walls of the cells are roughcast and in most there are no pictures or adornments. On the four corners of the construction there are four square brick pipes, through which the gas burning inside the temple exited. In the dome above the centre, above the fire well, there was a small iron hook, to which, at one time, a copper bell was attached.

Across the whole roof, which forms a closed pentagon, there are holes above every cell to allow gas and smoke to exit. The ceiling of every cell has a small round vault. There are no windows in the cells, the entrance door is low and has an arrow-shaped arch. There are inscriptions engraved above the entrance of every cell. In almost every cell where the Indian fire-worshippers used to live, there are small rises on the side walls, like sleeping ledges. In cell no. 13 there are 4 stone rings on the yard side wall for tying horses; there are 6 similar rings inside the cell and near them, cut into the same wall, there are 7 stone cribs for feeding horses. In a square of five cells, on top of 4 arrow-shaped arches, there is a round cupola; there were shrines in these cells. In all, there are twenty inscriptions above the cells and one of them is in Persian. In cell no. 19, on the inner side of the wall, there are faint traces of plant motifs, done in red paint; there are also traces of a picture in green paint. On the roughcast of the other wall of the same cell, one can see a rough picture in red paint. The picture depicts a goddess with six raised hands. The goddess is standing on an animal (a cow?). There are traces of red paint in various places under the roughcast of cell number 10. Near the temple, to the north-east, there is a four-sided hole, which is now completely full of rocks, where the bodies of the dead were burnt on the sacred fire. There is another water-well to the south-east of the temple, which is also completely filled with rocks. On the upper side of the outer wall of the temple there is a parapet decorated with dentils - very characteristic of Indian architecture.

From the above description it is clear that the Ateshgah in Surakhani is composed of 1) a temple, 2) monastic cells for ascetic Indians and 3) places for visiting guests. The outer blank wall which unites all the cells and buildings of the Ateshgah gives it the appearance of an ancient Persian caravanserai. It seems that Ateshgah was constructed by local masters working to a plan from the Indians who commissioned this monument.

The history of Atashgah goes back to the time of the Sassanids, when Zoroastrianism was the main religion in this region. But in 643 there was a crisis – the army of the Arab caliphate invaded the Caucasus, bringing Islam with it. The fire temples went into decline. Some of the fire-worshippers did not accept Islam and were eventually forced to return to India, where the history of the fire religion continued. A part of the population of the Caucasus remained fire worshippers after the introduction of Islam. Al-Istahri (10th century) wrote that fire-worshippers lived not far from Baku (on the Absheron Peninsula). This is backed up by Moisey (Moses) Kalankatuysky who mentioned the province of Bagavan – “Land of Gods” (ie. fire worshippers), as well as by archaeological evidence.

The economic relations existing between Azerbaijan and India in ancient times and the Middle Ages conditioned the development of cultural relations in the fields of philosophy, poetry, literature, architecture, art and music. This was particularly the case between the 16th and18th centuries, during the rule of the Mongolian Empire’s Baburid Dynasty in India. At the end of the 18th century and through the 19th century, during the British colonial invasion of India, the loss of independence and British rule interrupted these developments.

Economic and cultural relations between Azerbaijan and India began to prosper again following the independence of the Republic of Azerbaijan.

Literature

1. Kamil Farhadoglu. Baku Icheri Sheher. - Baku, 2006

2. Ashurbeyli. S.B. The history of the Surakhani fire-worshippers’ temple // The architectural monuments of Azerbaijan. - V.1. M., 1946

3. Ashurbeyli S.B. Indian merchants in the medieval cities of Azerbaijan and Shirvan. - People of Asia and Africa, No 4, Moscow, 1964

4. Ashurbeyli S.B. Essay on the history of medieval Baku. - Baku, 1964

5. Ashurbeyli S.B. Economic and cultural bonds between Azerbaijan and India in the Middle Ages. - “Elm” Publishing House, Baku, 1990

6. Qiyasi J.A. On the international relations of medieval Azerbaijani architects. - Baku, 1985

7. Leviatov V.N. Archaeological excavation of the Shirvanshah’s Palace in Baku City in 1945. – Academy of Sciences of the Azerbaijani SSR, 1948, No. 1

8. Mehsninov I.I. Egypt and the Caucasus. - Baku, 1927

9. Musayev T.Q. Some historical questions about Azerbaijan and India. - Baku, 1960.

10. Seyidzadeh A.A. From the history of cultural relations between Azerbaijan and India in the Middle Ages. – Academy of Sciences of the Azerbaijani SSR, public sciences series, 1958, No. 1

11. Useynov M.L., Bretanitskiy A., Salamzadeh A. A history of Azerbaijani Architecture. - M., 1963

by Kamil Ibrahimov

Relations between India and Azerbaijan extend back to ancient times; however they were particularly strong in the Middle Ages. Historically, the celebration of Baku as the city of “sacred fires” was a significant feature of Indian-Azerbaijani relations. It is known that Azerbaijan practised fire-worship and Christianity before the Arab invasion and there were many religious centres or shrines. One of the main centres of fire-worship was ancient Baku. It is widely known that in the early Middle Ages, Baku was already being mentioned as the location of eternal fires. The first such reference was made by a Byzantine author of the 5th century. This information surely refers to Baku’s eternal flames, to the sea shore and, it seems, to the fires at Surakhani and on Pirallahi Island. Writers in the Middle Ages and later mentioned the displays of combustible gas on the Absheron Peninsula – on Pirallahi Island, in Surakhani village, in Baku Bay and on Shubani Mountain. The strongest gas vents were in Surakhani village. Atesh-I Bagavan was mentioned by Gevond in the 8th century as Ateshi-Baguan, which means “fires of Bagavan”, “fires of the city of God” and which was located in the area around Baku. Absheron, bursting with oil and streams of combustible gas, was also included in the province of Paytakaran. The name Ateshi-Bagavan may have been connected with the sanctuaries and ancient temples of fire-worshippers, which existed in the Baku area or on Absheron in ancient times.

Archaeological evidence.

Trading relations clearly existed between Azerbaijan and India in ancient times, many centuries before Christ. Various findings of cowrie shells and other archaeological information testify to this. Cowries have been found in great quantities at burial sites in the settlements (Mingachevir) and cities of Azerbaijan and they are believed to originate in the Bronze Age (end of the second, beginning of the first millennium B.C.) The cowrie, as is known, is abundant in the Indian and Pacific oceans, and its use as coinage can be traced in India and neighbouring countries from the furthest past. In the process of barter trade, these shells served as common currency, through which barter was conducted.

Cowries, widely used in Azerbaijan, appeared here from India by sea, via Iran. They served as amulets, talismans etc. Ancient writers claim that there was a water way from the borders of Iran to upstream of the Rioni River, through the Black Sea and the navigable rivers of Central Asia, through the Caspian Sea, to the Kur River and Caucasian Albania.

English merchants bought cowries in India and, later, sold them in Guinea for twice or three times the price. There were very extensive trading operations in Central and Western Africa at that time, and they were transacted using cowrie shells.

Let’s take a look at some of the archaeological information testifying to the cult of fire and the expansion of fire-worship in Azerbaijan. An arched monument discovered in Icheri Sheher (Baku’s Old City) in 1964, is the yard of a mosque, cleared in 1989, near Maiden Tower. The mosque is a monument from the tenth century. An octagonal and triple-stepped pedestal, made of stone, and an octagonal column were discovered by the archaeologist O.S.Ismizadeh in the yard of the ancient temple. This construction was not destroyed during the construction of the mosque, and has survived to our time. The repetition of octagonal motifs is of great interest. The column at the centre of the monument seems to have served as a torch-holder during religious ceremonies.

The triple-stepped and octagonal pedestal, the octagonal column and other signs of antiquity prove once more that Baku was already inhabited in those ancient times. The fact that the city was inhabited by fire-worshippers is not in the slightest doubt.

Three metallic bronze cast items were discovered within the grounds of the Shirvanshahs’ Palace in Baku during archaeological excavations; they were in layers of sand, 2.4 metres below the modern surface. One of them is a wide, shallow, open cup on a stand (height 8.8 cm) with its outer surface decorated with borders. The two other items are lamps: one 12.9 cm high, the other 10.7 cm. These items have an ancient appearance. “The position in which they were discovered (laid next to each other in a layer of clear sand) indicates that they had probably been hidden”. Their shapes are similar to those in a picture on a signet ring from Mingachevir and refer to a pre-Islamic period; we may assume that they are connected to the cult of fire and fire-worship. The Arabs followed the Zoroastrians and people of other faiths, and impressed Islam upon those who resisted.

As we know, fire-worship was prevalent in the second half of the first millennium in Absheron and Christianity was widespread in the early Middle Ages in Shirvan, Mughan, Lenkeran, the Talysh region, South Azerbaijan and in the north of Azerbaijan. In several regions the most ancient cults have been preserved – the cults of rock, wood, moon and sun worship etc.

The Indian “Multana” caravanserai.

In the 15th century, a colony of Indian merchants lived and had caravanserais in Baku, Shemakha, Tabriz and other Azerbaijani cities. The 15th century Indian Multana caravanserai still stands in the ancient fortress of Baku – Icheri Sheher. Trading by Indian merchants, who mainly bought raw silk produced in Shirvan, Shemakha and other places, continued in Azerbaijan until the 16th century and later.

About 50 m north-west of the Baku temple, Maiden Tower, there is a caravanserai building – totally reconstructed in the 14th century on the foundations of a more ancient construction - which had obviously served the same purpose. This building still carries its ancient name – the “Multana” caravanserai, taking the name of an Indian tribe of fire-worshippers. It seems that the name was given to the caravanserai in the 15th century, inherited from its more ancient predecessor, built in times of rigorous Zoroastrianism - the Sassanid era, or even earlier; it is hard to imagine that any building could have been given a pagan name while Islam held sway. This caravanserai was restored again in the 17th century and the last major work carried out on it was a reconstruction from 1974-1976.

Constructed right next to the high stone wall surrounding the temple, not far from the main gates, which were located a little further west, the Multana caravanserai served as a shelter for Zoroastrian pilgrims from far India. The Indian pilgrims often came to the ancient city of Ateshi-Baguan and stayed at their caravanserai to participate in worship and sacrificial offerings at the principal temple of the Mazdaites - and later the Zoroastrians - the Baku temple of seven-headed fires.

The temples of Baku were clearly visited by followers of the Zoroastrian religion. Opposite the caravanserai for Indian fire-worshippers was the Bukhara caravanserai for merchants from Central Asia. The latter had been reconstructed in the 15th century on the site of an older building which had probably been a shelter for fire-worshippers from Sogda, Khorezm and Bactria. It would seem that these caravanserais enabled merchants from distant countries to combine business with worship of their God in the cult complex. While the flames continued to burn in the Baku, the temple complex of the ancient city of Ateshi-Baguan was probably the main cult centre of Mazdaism and Zoroastrianism, popular across Caspiana, Albania and Midia – Atropatena,

Baku Juma – Cathedral Mosque.

It is no coincidence that some people in Baku still believe that the Juma Mosque, located within Baku’s Old City walls, was built on the site of an ancient fire-worshippers’ temple. A traveller, who saw the Baku Juma Mosque in 1873, described four arches in the middle of the mosque; their tops did not overlap. Those arches were ancient shrines; they had been preserved from the ancient temple of fire-worshippers and reconstructed into a Muslim mosque. Thus, the temple was open on all four sides and topped by a cupola. In the middle there was a hole/well, where fire – combustible gas - burned continuously. A writer who visited the Juma Mosque in 1887 compared it to the fire temple in Surakhani.

Ateshgah.

One of the most interesting and peculiar historical monuments near Baku is the fire temple of Indian fire-worshippers, called Ateshgah. It is located on a flat area not far from the sea, to the south-east of the village of Surakhani on the Absheron Peninsula; it is currently surrounded by oil fields on all sides. The cells and the temple were constructed at different times between the 17th and 19th centuries. The cells were enclosed within a surrounding wall at the end of the 18th century. Ateshgah was constructed by Indians living in Baku, the majority of whom came from Northern India and were members of the Sikh community.

All the buildings, reminiscent of a caravanserai, are designed as a closed pentagon and consist of 24 cells and rooms, which used to accommodate visiting pilgrims. The entrance is two-storeyed; on the second floor is a room with two windows and a door between them in the northern and southern walls and a door in the short eastern and western walls. This place for visiting guests was called the “balahane”. There is a stone staircase from the balahane into the internal yard. On the outer wall of this room there is some Indian writing. There is more Indian writing on the ground floor above the entrance door. On the four corners of the flat roof of the balahane there are four stone pipes, where fire used to burn. Inside the yard, enclosed within a walled pentagon, is the temple-shrine in the form of a rotunda, in the middle of which there was a well, where the gas (methane) flamed; it also burned above the cupola at the four corners of the building. The shrine itself is a four-sided construction, open on all sides, which means it consists of four rectangular columns, joined by arches and topped by a cupola. The walls of the shrine are covered by finely-shaped medium-size limestone plates. On the northern wall of the shrine, facing the balahane, there is some Indian writing above the arch. The inner walls of the cells are roughcast and in most there are no pictures or adornments. On the four corners of the construction there are four square brick pipes, through which the gas burning inside the temple exited. In the dome above the centre, above the fire well, there was a small iron hook, to which, at one time, a copper bell was attached.

Across the whole roof, which forms a closed pentagon, there are holes above every cell to allow gas and smoke to exit. The ceiling of every cell has a small round vault. There are no windows in the cells, the entrance door is low and has an arrow-shaped arch. There are inscriptions engraved above the entrance of every cell. In almost every cell where the Indian fire-worshippers used to live, there are small rises on the side walls, like sleeping ledges. In cell no. 13 there are 4 stone rings on the yard side wall for tying horses; there are 6 similar rings inside the cell and near them, cut into the same wall, there are 7 stone cribs for feeding horses. In a square of five cells, on top of 4 arrow-shaped arches, there is a round cupola; there were shrines in these cells. In all, there are twenty inscriptions above the cells and one of them is in Persian. In cell no. 19, on the inner side of the wall, there are faint traces of plant motifs, done in red paint; there are also traces of a picture in green paint. On the roughcast of the other wall of the same cell, one can see a rough picture in red paint. The picture depicts a goddess with six raised hands. The goddess is standing on an animal (a cow?). There are traces of red paint in various places under the roughcast of cell number 10. Near the temple, to the north-east, there is a four-sided hole, which is now completely full of rocks, where the bodies of the dead were burnt on the sacred fire. There is another water-well to the south-east of the temple, which is also completely filled with rocks. On the upper side of the outer wall of the temple there is a parapet decorated with dentils - very characteristic of Indian architecture.

From the above description it is clear that the Ateshgah in Surakhani is composed of 1) a temple, 2) monastic cells for ascetic Indians and 3) places for visiting guests. The outer blank wall which unites all the cells and buildings of the Ateshgah gives it the appearance of an ancient Persian caravanserai. It seems that Ateshgah was constructed by local masters working to a plan from the Indians who commissioned this monument.

The history of Atashgah goes back to the time of the Sassanids, when Zoroastrianism was the main religion in this region. But in 643 there was a crisis – the army of the Arab caliphate invaded the Caucasus, bringing Islam with it. The fire temples went into decline. Some of the fire-worshippers did not accept Islam and were eventually forced to return to India, where the history of the fire religion continued. A part of the population of the Caucasus remained fire worshippers after the introduction of Islam. Al-Istahri (10th century) wrote that fire-worshippers lived not far from Baku (on the Absheron Peninsula). This is backed up by Moisey (Moses) Kalankatuysky who mentioned the province of Bagavan – “Land of Gods” (ie. fire worshippers), as well as by archaeological evidence.

The economic relations existing between Azerbaijan and India in ancient times and the Middle Ages conditioned the development of cultural relations in the fields of philosophy, poetry, literature, architecture, art and music. This was particularly the case between the 16th and18th centuries, during the rule of the Mongolian Empire’s Baburid Dynasty in India. At the end of the 18th century and through the 19th century, during the British colonial invasion of India, the loss of independence and British rule interrupted these developments.

Economic and cultural relations between Azerbaijan and India began to prosper again following the independence of the Republic of Azerbaijan.

Literature

1. Kamil Farhadoglu. Baku Icheri Sheher. - Baku, 2006

2. Ashurbeyli. S.B. The history of the Surakhani fire-worshippers’ temple // The architectural monuments of Azerbaijan. - V.1. M., 1946

3. Ashurbeyli S.B. Indian merchants in the medieval cities of Azerbaijan and Shirvan. - People of Asia and Africa, No 4, Moscow, 1964

4. Ashurbeyli S.B. Essay on the history of medieval Baku. - Baku, 1964

5. Ashurbeyli S.B. Economic and cultural bonds between Azerbaijan and India in the Middle Ages. - “Elm” Publishing House, Baku, 1990

6. Qiyasi J.A. On the international relations of medieval Azerbaijani architects. - Baku, 1985

7. Leviatov V.N. Archaeological excavation of the Shirvanshah’s Palace in Baku City in 1945. – Academy of Sciences of the Azerbaijani SSR, 1948, No. 1

8. Mehsninov I.I. Egypt and the Caucasus. - Baku, 1927

9. Musayev T.Q. Some historical questions about Azerbaijan and India. - Baku, 1960.

10. Seyidzadeh A.A. From the history of cultural relations between Azerbaijan and India in the Middle Ages. – Academy of Sciences of the Azerbaijani SSR, public sciences series, 1958, No. 1

11. Useynov M.L., Bretanitskiy A., Salamzadeh A. A history of Azerbaijani Architecture. - M., 1963