Pages 24-30

by Kamil Farhadoglu

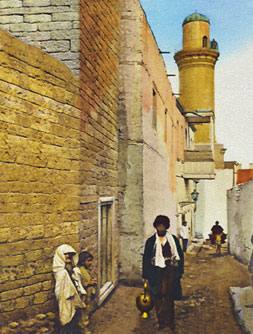

All of Baku used to be located within the area of the presentday Icheri Sheher, i.e. actually Baku was Icheri Sheher. In the first half of the 19th century, the city began to grow and expand beyond the fortress walls.

As a result, the fortress came to be called “Icheri Sheher” (Inner City) and what was outside was the “Outer City”.

When Icheri Sheher was being built in the Middle Ages, it consisted of twisting streets which defi ned small neighbourhood areas – there were nine in all. Each area centred on its mosque: the Juma mosque, Shah mosque, Mahammadyar mosque, Haji Qayib mosque, Hamamchilar mosque, Siniqqala mosque, Qasim bay mosque etc. Each had its own mullah.

by Kamil Farhadoglu

All of Baku used to be located within the area of the presentday Icheri Sheher, i.e. actually Baku was Icheri Sheher. In the first half of the 19th century, the city began to grow and expand beyond the fortress walls.

As a result, the fortress came to be called “Icheri Sheher” (Inner City) and what was outside was the “Outer City”.

When Icheri Sheher was being built in the Middle Ages, it consisted of twisting streets which defi ned small neighbourhood areas – there were nine in all. Each area centred on its mosque: the Juma mosque, Shah mosque, Mahammadyar mosque, Haji Qayib mosque, Hamamchilar mosque, Siniqqala mosque, Qasim bay mosque etc. Each had its own mullah.

Each to his own

Some of the areas were named after people who had arrived in Baku and settled in Icheri Sheher. The Gilaklar block was occupied by merchants who had arrived from Gilan. Gunsmiths from Dagestan lived in the Lezgi block.

Most of the population of Icheri Sheher were craftsmen, merchants or sailors.

Some areas were named after the professions of the craftsmen who lived there.

The Hamamchilar (bathhouse workers), Bazzazlar (leather workers), Hakkakchilar (engravers) etc. The people of Icheri Sheher – Azerbaijanis – also fell into various clans. Some of them had very interesting names.

The White-trousers, the Chicken-eaters, the No-Chickens, the Greyheads etc. The Greyheads were so called because their hair went grey early and the White-trousers got their name because they were seamen – and there were various jokes about them. In the past, everyone living in Icheri Sheher had a nickname. Although sometimes these nicknames were quite funny, they did not off end people or cause them to object. At one time there are known to have been four people living there who carried the name Haji Zeynalabdin.

Each had a nickname: Plasterer, Mule, Thank-you, No-Cheese. Or Agamali, always ready to give a helping hand, was nicknamed Shortie because he was.... not very tall.

The first shopping mall?

There was a large bazaar in Icheri Sheher, one edge running from the Juma mosque past Maiden Tower towards the Qosha Qala gate (Double Gates), the other end stretching from Maiden Tower towards a street that ran down to the sea. This bazaar was divided into two parts: the area around the Juma mosque was called Ashagibazar (Lower) and the area near Maiden Tower was called Yukharibazar (Upper). Yukharibazar was also called the covered

bazaar because most of the shops there, in the part that ran from Maiden Tower to the Chukhur caravanserai (a two-storey caravanserai), were under cover. The shops faced each other in two rows and were located inside a roofed building – big merchants and money-changers operated here. Ashagibazar housed petty traders, grocers, tailors and hat-makers, while Yukharibazar housed dealers in cloth.

Although in 1806 there were 7,000 people living in Icheri Sheher, there were actually 707 shops and craftwork shops. Every merchant and skilled craftsman had his own shop. The buyers were merchants arriving in Baku from various towns. Ships carried goods between Baku and Iran, Central Asia and Russia.

Although in 1806 there were 7,000 people living in Icheri Sheher, there were actually 707 shops and craftwork shops. Every merchant and skilled craftsman had his own shop. The buyers were merchants arriving in Baku from various towns. Ships carried goods between Baku and Iran, Central Asia and Russia.

Leisure...

There were many medieval hamams (bathhouses) in this walled city. Residents of ancient Baku loved to go and relax in them. As well as bathing, they could have cool sherbert or hot tea, eat a dessert or smoke shisha (hookah). Some of Icheri Sheher’s hamams are still there. These include the Haji Bani (Qayib) hamam, the Haji Mikayil hamam and the Qasimbey hamam, which are close to Maiden Tower and date between the 15th and 18th centuries.

...sport

Another of the entertainment centres in Icheri Sheher was the sports hall – zorkhana – where athletic competitions were held. Baku’s zorkhana dates back to the 15th century. This underground building, with an arched ceiling, was located near Maiden Tower, a few steps from the Bukhara and Multani caravanserais. As in present-day gyms, men paid an entry fee to enter zorkhanas to take part in various contests, including weight lifting and wrestling. Some contests were accompanied by a trio of musicians playing the traditional oriental musical instruments kamancha, zurna and nagara. Although many of the songs played back then have been lost, one of them – “Jangi” – is still played before and after national wrestling contests.

Zorkhanas appeared in Baku under the Safavid dynasty; they encouraged sports in all possible ways in order to keep future warriors in good physical shape. This is where they trained pahlavans – champions - in weightlifting and wrestling. The title of pahlavan was confirmed by a special paper and the pahlavan himself was invited to the court of the Shirvanshahs. The pahlavans were led by a pahlavanbashi. In modern understanding, zorkhana fulfilled the function of a sports palace and a gym and there was one in almost every neighbourhood of the city. Sometimes hamams were rented out for use as zorkhanas.

A traveller described one of Baku’s zorkhanas at the end of the 18th century. There was one for 300 spectators, closed down by the tsarist government only in 1893. In the middle of the zorkhana was a round sports pitch with a diameter of about 10 metres and 1 metre deep, called a sufra. The sufra was first filled with dry grass, then with ash and, finally, with softearth. Some 20-25 people could work out there simultaneously. They wore leather trousers of an original style, called tanban. Around the sufra were seats for spectators. An instructor – murshid – sat on an elevation not far from the sufra. A small bell hung above him. Contests started and ended with the ringing of this bell. It also interrupted competitions when rules were broken.

The stuff y air, a normal hazard in gyms, was improved by burning dry aromatic grasses on a grill placed near the murshid. All exercises and contests were conducted to the music of the dumbek (hand drum), qosha zurna and tutek (wind instruments). There were regular melodies – eg. Koroglu - and poems and heroic sagas were recited. Wrestling has long been a very popular sport in Baku. Men competed not only in zorkhanas, but also outdoors on soft land or on large carpets. No holiday, no festivity, passed without wrestling contests. The combatants wore the short trousers and were bare-chested. They covered their bodies in oil mixed with henna. Famous pahlavans often acted as referees.

Zorkhanas appeared in Baku under the Safavid dynasty; they encouraged sports in all possible ways in order to keep future warriors in good physical shape. This is where they trained pahlavans – champions - in weightlifting and wrestling. The title of pahlavan was confirmed by a special paper and the pahlavan himself was invited to the court of the Shirvanshahs. The pahlavans were led by a pahlavanbashi. In modern understanding, zorkhana fulfilled the function of a sports palace and a gym and there was one in almost every neighbourhood of the city. Sometimes hamams were rented out for use as zorkhanas.

A traveller described one of Baku’s zorkhanas at the end of the 18th century. There was one for 300 spectators, closed down by the tsarist government only in 1893. In the middle of the zorkhana was a round sports pitch with a diameter of about 10 metres and 1 metre deep, called a sufra. The sufra was first filled with dry grass, then with ash and, finally, with softearth. Some 20-25 people could work out there simultaneously. They wore leather trousers of an original style, called tanban. Around the sufra were seats for spectators. An instructor – murshid – sat on an elevation not far from the sufra. A small bell hung above him. Contests started and ended with the ringing of this bell. It also interrupted competitions when rules were broken.

The stuff y air, a normal hazard in gyms, was improved by burning dry aromatic grasses on a grill placed near the murshid. All exercises and contests were conducted to the music of the dumbek (hand drum), qosha zurna and tutek (wind instruments). There were regular melodies – eg. Koroglu - and poems and heroic sagas were recited. Wrestling has long been a very popular sport in Baku. Men competed not only in zorkhanas, but also outdoors on soft land or on large carpets. No holiday, no festivity, passed without wrestling contests. The combatants wore the short trousers and were bare-chested. They covered their bodies in oil mixed with henna. Famous pahlavans often acted as referees.

...and culture

Icheri Sheher’s cultural life was also very rich. Residents liked attending sports contests, poetry gatherings and mugham nights. Poets, musicians and others got together, recited lyric poems (rubais and ghazals) and listened to mugham music. Food, drinks and sweets would be served. Normally, mugham is performed by an ensemble consisting of a singer – khanende - a tar (double-bodied, long-necked lute) player and a kamancha (bowed lyre) player. The khanende holds in his hand a daf (tambourine- like drum) and uses it, when singing, as a resonator and sound reflector targeted at the audience, and also maintains the rhythm in instrumental parts of the performance.

The main melody is led by the tar, while the kamancha repeats this melody with a slight delay. Sometimes the number of instruments accompanying the singing of the khanende is increased. The traditions of performing mugham as a trio apparently go back to olden times, as a 17th-century German traveller, Adam Olearius, has a description of a musical gathering in Shemakha, at which a mugham trio performed.

In their free time, the local population would sometimes go hunting for hares with greyhounds. Icheri Sheher youth were also pigeon-fanciers. They kept lots of pigeons in special huts, and sometimes under the roofs of residential houses. Every morning they would go up to the roof, feed the pigeons and then whistle them out to fly.

When the heat arrived, Bakuvians headed off on ancient carts to their Absheron dachas (summer houses). The cart carried bedding and was decorated in festive manner with wall or floor carpets, with pillows and cushions scattered on top of them. The women and children were placed on this soft bed. The men accompanied the cart on horses. With the appearance of the suburbs, the carts were partially replaced by chariots.

The main melody is led by the tar, while the kamancha repeats this melody with a slight delay. Sometimes the number of instruments accompanying the singing of the khanende is increased. The traditions of performing mugham as a trio apparently go back to olden times, as a 17th-century German traveller, Adam Olearius, has a description of a musical gathering in Shemakha, at which a mugham trio performed.

In their free time, the local population would sometimes go hunting for hares with greyhounds. Icheri Sheher youth were also pigeon-fanciers. They kept lots of pigeons in special huts, and sometimes under the roofs of residential houses. Every morning they would go up to the roof, feed the pigeons and then whistle them out to fly.

When the heat arrived, Bakuvians headed off on ancient carts to their Absheron dachas (summer houses). The cart carried bedding and was decorated in festive manner with wall or floor carpets, with pillows and cushions scattered on top of them. The women and children were placed on this soft bed. The men accompanied the cart on horses. With the appearance of the suburbs, the carts were partially replaced by chariots.

Eat, drink...

The people of Icheri Sheher have always maintained the tradition of helping the poor. During Muslim religious holidays and periods of mourning, rich people (and even the not so rich) gave a “commemorative repast” to the poor or invited them to meals. On holidays and days of mourning, commemorative meals were made in hundreds of homes in Baku. Merchants sometimes laid out commemorative repasts in front of their shops.

The food in Icheri Sheher was also distinctive: the rich sweetmeat baklava was thicker than in other regions, with more layers, and Absheron saffron was used much more liberally in diff erent dishes. Icheri Sheher residents loved meat and sometimes referred to it as “jan” (a term of endearment – ‘my soul’). Along with the ubiquitous teahouses, there were the taverns (meykhana and kharabat) where one could have a glass of wine, smoke shisha, talk to friends, listen to music or ashugs (troubadours) and play games. Christians brought the wines that they made in Shemakha.

Distinctive of Baku meykhanas (winehouses) were poetry contests between tavern regulars. Verses were created spontaneously to the rhythmic accompani- ment of a daf. The theme was set by one of the participants, after which an improvised jocular-satirical contest began. Presumably, Sufi dervishes held their meetings in meykhanas. Excited by wine and rhythmic poems, they reached a religious trance. These places were regularly closed down by the clerics; they closed and reopened depending on the political situation in the country. Poetry contests, however, became so popular that they began to be held outside taverns – on holidays and at weddings, but they are still known as meykhana. Professional meykhana performers appeared who were (and are still) acknowledged and invited to perform at weddings, for a fee.

The food in Icheri Sheher was also distinctive: the rich sweetmeat baklava was thicker than in other regions, with more layers, and Absheron saffron was used much more liberally in diff erent dishes. Icheri Sheher residents loved meat and sometimes referred to it as “jan” (a term of endearment – ‘my soul’). Along with the ubiquitous teahouses, there were the taverns (meykhana and kharabat) where one could have a glass of wine, smoke shisha, talk to friends, listen to music or ashugs (troubadours) and play games. Christians brought the wines that they made in Shemakha.

Distinctive of Baku meykhanas (winehouses) were poetry contests between tavern regulars. Verses were created spontaneously to the rhythmic accompani- ment of a daf. The theme was set by one of the participants, after which an improvised jocular-satirical contest began. Presumably, Sufi dervishes held their meetings in meykhanas. Excited by wine and rhythmic poems, they reached a religious trance. These places were regularly closed down by the clerics; they closed and reopened depending on the political situation in the country. Poetry contests, however, became so popular that they began to be held outside taverns – on holidays and at weddings, but they are still known as meykhana. Professional meykhana performers appeared who were (and are still) acknowledged and invited to perform at weddings, for a fee.

...and marry

A Baku wedding was festive but solemn in nature from the first day to the last. There were many participants involved in the wedding rite. Throughout the wedding cycle, relatives, friends, neighbours, and fellow-townspeople

joined in as active organizers in all the festivities and rites, up to preparing the wedding food. The wedding cycle was in three parts: prewedding, the wedding – ‘toy’, and postwedding. The pre-wedding period consisted of several stages – selection of the girl, preliminary betrothal, formal marriage proposal, engagement, the rite of designing the bride’s wedding dress, the rite of henna-dying etc.

Islam forbade a girl from appearing in men’s company with her face uncovered and this compelled the groom to trust to his relatives’ judgement. Therefore, having heard about her son’s wish to get married, his mother, along with several other women, used a pretext to visit the girl he selected. The young man might learn about the girl from his sisters or remember her from games they played as children. In other cases, the selection process involved a go-between, who would inquire into the young man’s prospects and collect information about the proposed bride. The reluctance of young people to enter a ‘blind’ marriage may explain why in the old days there were numerous marriages between cousins among Bakuvians.

After the bride’s parents had given their consent for matchmakers to visit them, a formal proposal of marriage was made. The team of matchmakers normally included the groom’s father and mother, the groom’s maternal uncle, the groom’s paternal uncle, his elder brother, and close relatives and respected people of the town from among friends or neighbours. After the successful completion of matchmaking discussions, the two sides (the fathers) ate bread and salt, which symbolised the coming together of the two families.

The formal proposal of marriage was followed by engagement. The nishan (engagement) was held in the bride’s house, soon after the formal proposal of marriage. A large group of the groom’s relatives and close acquaintances visited the bride’s house with presents for her.

Islam forbade a girl from appearing in men’s company with her face uncovered and this compelled the groom to trust to his relatives’ judgement. Therefore, having heard about her son’s wish to get married, his mother, along with several other women, used a pretext to visit the girl he selected. The young man might learn about the girl from his sisters or remember her from games they played as children. In other cases, the selection process involved a go-between, who would inquire into the young man’s prospects and collect information about the proposed bride. The reluctance of young people to enter a ‘blind’ marriage may explain why in the old days there were numerous marriages between cousins among Bakuvians.

After the bride’s parents had given their consent for matchmakers to visit them, a formal proposal of marriage was made. The team of matchmakers normally included the groom’s father and mother, the groom’s maternal uncle, the groom’s paternal uncle, his elder brother, and close relatives and respected people of the town from among friends or neighbours. After the successful completion of matchmaking discussions, the two sides (the fathers) ate bread and salt, which symbolised the coming together of the two families.

The formal proposal of marriage was followed by engagement. The nishan (engagement) was held in the bride’s house, soon after the formal proposal of marriage. A large group of the groom’s relatives and close acquaintances visited the bride’s house with presents for her.

Ceremony

The wedding consisted of an artistic celebration (music, dancing, singing, games, and poem and saga recitals) and a feast. More often than not, there was no feast as such. The guests were given food in a special room (it was also there that the guest contributed their monetary present), after which they went to the premises where the wedding was to be held. As a rule, large marquees were used to celebrate weddings, with expensive carpets laid in them. There was no food, except for sweets and a selection of nuts distributed to guests on special trays. Alcohol was out of the question. The appearance of musicians announced the

start of proceedings. The musicians would be at the gate to the house, or on the roof. The wedding was celebrated first in the bride’s house and then in the groom’s house, by men and women separately.

The female part of a Baku wedding normally lasted two days, while the male part lasted two or three days and, in some cases and in wealthy families, seven days. Each wedding day had a name and purpose. Musicians, singers, sometimes ashugs, and boy dancers dressed in women’s costumes, were invited. A wedding in old Baku resembled a traditional Azerbaijani musical gathering. A khanende prepared specially for the occasion, as Bakuvians knew well the subtleties of mugham and not all singers were acceptable. Sometimes two mugham trios were invited or, later, ensembles of musicians who had become fashionable, and there was implicit competition.

Wealthy families invited famous singers and musicians from other towns of Azerbaij an and even from Iran. After the wedding, people in the city would discuss the wedding concert and the khanende’s performance for a long time. Before the start of the wedding festivities, the ceremony was finalised. To this end, two trusted persons from each side went to a mullah who conducted the marriage ceremony. This included a listing of items that the groom presented to the bride and also a listing of her dowry. An invariable component of the wedding was a public inspection of the dowry by the groom’s close relatives.

In addition to an agreed fee, the musicians also received money that guests gave to those dancing, as well as a tray of sweets and small presents, also from the guests. Music, dancing and singing accompanied the wedding ceremony until the end, i.e. until the bride was resettled to her husband’s house Invariable elements of Baku weddings were various competitive games and amusements (horse racing, wrestling, archery, javelin throwing etc). The youth prepared in advance for the horse racing, wrestling and other contests and looked forward to them eagerly. The winners enjoyed great respect in the city and villages and received generous presents from the organizers of the wedding and guests.

Distinctive features of a Baku wedding were the gathering of men on the night before the wedding and a meykhana contest between participants and professional meykhana performers upon completion of the wedding. On that night, the men played gambling games, drank tea and smoked shisha. Sometimes famous Baku qochus were invited to the wedding to watch order.

The female part of a Baku wedding normally lasted two days, while the male part lasted two or three days and, in some cases and in wealthy families, seven days. Each wedding day had a name and purpose. Musicians, singers, sometimes ashugs, and boy dancers dressed in women’s costumes, were invited. A wedding in old Baku resembled a traditional Azerbaijani musical gathering. A khanende prepared specially for the occasion, as Bakuvians knew well the subtleties of mugham and not all singers were acceptable. Sometimes two mugham trios were invited or, later, ensembles of musicians who had become fashionable, and there was implicit competition.

Wealthy families invited famous singers and musicians from other towns of Azerbaij an and even from Iran. After the wedding, people in the city would discuss the wedding concert and the khanende’s performance for a long time. Before the start of the wedding festivities, the ceremony was finalised. To this end, two trusted persons from each side went to a mullah who conducted the marriage ceremony. This included a listing of items that the groom presented to the bride and also a listing of her dowry. An invariable component of the wedding was a public inspection of the dowry by the groom’s close relatives.

In addition to an agreed fee, the musicians also received money that guests gave to those dancing, as well as a tray of sweets and small presents, also from the guests. Music, dancing and singing accompanied the wedding ceremony until the end, i.e. until the bride was resettled to her husband’s house Invariable elements of Baku weddings were various competitive games and amusements (horse racing, wrestling, archery, javelin throwing etc). The youth prepared in advance for the horse racing, wrestling and other contests and looked forward to them eagerly. The winners enjoyed great respect in the city and villages and received generous presents from the organizers of the wedding and guests.

Distinctive features of a Baku wedding were the gathering of men on the night before the wedding and a meykhana contest between participants and professional meykhana performers upon completion of the wedding. On that night, the men played gambling games, drank tea and smoked shisha. Sometimes famous Baku qochus were invited to the wedding to watch order.

“Protection”

The Icheri Sheher qochus were

stubborn, arrogant men who wore big moustaches, traditional clothes and who were armed with pistols and daggers. When they walked down the street, no-one dared face them. In the late 19th century, qochus kidnapped rich Baku residents. They emerged in response to Georgian bandits who robbed and threatened the rich and who were called “kintos”. As the city police could not cope with the kintos, rich people began to train strong, brave men and to arm them. The kintos soon disappeared from Baku and never returned. Recognising the benefi t of the qochus, Baku millionaires began to use them as private guards. If businesspeople became involved in a dispute, they would send their qochus to fight the other’s qochu. Sometimes this contest resulted in real shooting.

Round the mulberry

Behind the Juma mosque in Icheri Sheher, there was, and still is, a very large, old mulberry tree. People say that this tree is several hundred years old. On hot summer days, men will sit under it playing nard (backgammon) and drinking tea. The tree was so famous in the city that it was used as a landmark. There is another story that it was planted by the grandfather of Bahram Mansurov, one of Baku’s most respected tar players. This epitomises the enduring cultural traditions of Icheri Sheher, whose people take a special pride in their inner world and who try to preserve its historical character, monuments and atmosphere.