It would be fair to say that arriving in Baku almost three years ago presented me with a certain amount of culture shock. I’d expected to find a city similar to those in which I’d lived in Russia and experienced in other parts of the former USSR, but what I found had a much more Turkish, oriental or Middle Eastern feel. I couldn’t quite put my finger on it.

Since then, all the things that initially appeared as strange to me, such as the erratic drivers, kebabchi and chaykhanas, have gradually withered into normality. But it’s been a long journey. Baku is a city of many different layers and while it’s easy to be distracted by the bright lights and glitzy facades, another Baku inhabits an entirely different world - a world which unravels itself in tiny backstreets, bustling bazaars and behind old wooden doors.

Outsiders looking in

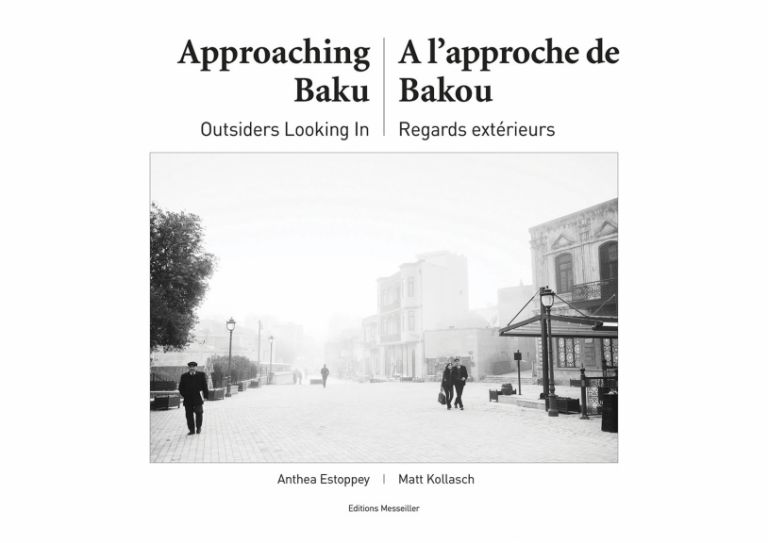

This is the world explored in a new photobook called Approaching Baku: Outsiders Looking In, a collaboration between Swiss journalist Anthea Estoppey and American photographer Matt Kollasch, both of whom lived in Baku between 2013 and 2016. The book was born out of their shared sense of “lost in translation,” as they attempted to dig beneath the surface of the city’s culture and traditions and met various obstacles along the way, beginning with simple things such as language:

We had this problem with the language, explained Estoppey in a recent interview, because when I came to Azerbaijan I thought people would speak Russian so I started learning Russian and I realised about three months later that people didn’t really understand me. I thought, ok, maybe it’s my pronunciation, maybe I don’t say the word properly, maybe my sentence structure is totally wrong and I realised that people didn’t really speak Russian, they were speaking Azerbaijani.

I thought, ok, maybe it’s my pronunciation, maybe I don’t say the word properly, maybe my sentence structure is totally wrong and I realised that people didn’t really speak Russian, they were speaking Azerbaijani

Difficulties communicating made the pair feel like outsiders viewing Baku from a distance, unable to understand the intricacies of its daily life despite living in the heart of the city, among its people. The idea to develop this into a book evolved organically following their first meeting through friends at the end of 2014. Estoppey had recently arrived but Kollasch had already been photographing the city for a year and a half. They conversed and it became clear they were thinking along similar lines:

She was interested in the same things but she was expressing them in words and I was expressing them in photographs, so it was nice that we met and had this conversation because I think that it really was a nice fit, Kollasch told me recently.

They met regularly throughout 2015 to discuss the difficult-to-penetrate world they were experiencing around them. Estoppey researched and wrote short vignettes while Kollasch edited his archive of images. He’d already taken most of the ones that made the book during his previous wanderings, but Estoppey also assigned him to find some to complement her writing.

A year and a half since the project began Estoppey was speaking from Cameroon and Kollasch from Kosovo, but it was clear that Baku and their book – the first for both – were still firmly on their minds: Actually when it was over I had a little bit of a let down, admitted Kollasch, who loved the intensity of the book-making process: It was a new experience for me to do something so heavily in such a short amount of time, with words and pictures.

Thematic approach

Approaching Baku: Outsiders Looking In blends over a hundred of Kollasch’s black and white photos with a collection of Estoppey’s descriptive essays exploring the curiosities of daily life, from the traffic jams that dance to their own peculiar rhythm, the steamy hammams and historic Sovietskiy to the gale-force winds, markets and troops of men playing nards.

Being invited into people’s homes, into their lives, was a huge part of how we could make the book

We talked about things that were fascinating for us, that we asked questions about, said Estoppey. For instance, the weddings, the young women… I was very curious to understand how and why the women feel the urge to marry so young… All the things in the book are the things we wanted to know more about, that we wanted to explore.

A lot of research that I did for the book was because I was interested in that. I wanted to know more, I wanted to understand how the traditions… for instance all the sheep being butchered in the street, I mean that’s really something that we don’t have anymore in Switzerland or in Europe in general and that was very interesting for me, because I wanted to understand how it was still happening, how come people are still living life that way…

Some of Estoppey’s questions remained unanswered but for others, such as the issue of young women feeling compelled to marry very young, she felt she found some answers. Although this happened less by asking questions and more through simply being among the people and entering their world: Being invited into people’s homes, into their lives, was a huge part of how we could make the book, she said.

Another topic the two were drawn to was the disappearing old quarter of Sovietskiy, which has gradually been demolished over the past few years to be redeveloped into wide roads and parks. Yet in Sovietskiy, like many curious expats, Estoppey and Kollasch encountered beauty among the rubble and interesting characters behind old wooden doors: Sovietskiy, I loved this area actually, this district. I loved this place, I loved walking there and seeing how the buildings were deconstructing and still people were living there and I felt that was so beautiful, so sad in a way but beautiful at the same time, said Estoppey.

Her use of the present tense adds immediacy and gives a sense of Come join me! as she explores the city’s rhythm, sights and sounds: I can still feel myself walking down my street in Azerbaijan, in Baku, I can still feel my neighbourhood, she told me, speaking from Cameroon and admittedly missing her former home.

I loved it! she said, looking back on her Azerbaijani experiences, having arrived with no fixed ideas and not knowing what to expect: I tried to be as neutral as possible while exploring the city and I loved it. What I liked the most was the fact that I was in security. I really felt that nothing could happen to me, Baku is really a safe place. Highlights of her time included drinking tea regularly in Icheri Sheher and trips to mountain villages such as Khinaliq and Lahij.

Interesting too is the bilingual nature of the book. Initially, the plan had been to make it in English but Estoppey, whose native language is French, felt that using both languages would reflect the reality of their mixed French- and English-speaking social circle in Baku. More importantly, however, It reinforces that we are the outsiders, we don’t even speak the same language! explained Estoppey, referring again to the central narrative of the book.

Exploring everyday life

Having spent most of his working life as a librarian, Kollasch rediscovered photography in the 1990s but Azerbaijan was the first time he’d been able to devote himself entirely to his passion: Baku was perfect for it, he explained. For me it’s a very walk-able city, it’s a city that invites you to explore it in my mind, especially on foot […] And when you’re walking you can see things and you start to notice things, and I would go round the back of courtyards and I would just poke around and get invited in for tea and meet people.

During this early stage Kollasch was pursuing a project about abandoned chairs and otherwise simply wanted to explore everyday life. And like Estoppey, he experienced some confusion at the culture he encountered: A lot of it was so new to me that I was often trying to understand it, because I saw it as a mix of… I don’t know… Azeri and Russian culture coming together.

The photographer was drawn to the old areas of Baku, particularly the area between Teze Bazaar and Besh Mertebe, rather than more touristy areas like Nizami Street and the Boulevard: I like neighbourhoods like that where there’s some street life, there’s some private homes, it’s old Baku, there’s normal people, schools. I was trying to look for daily life. You know I hardly ever photographed in Fountains Square. I tried […] but it just wasn’t interesting to me in the end.

During these walks he found Baku’s residents open to photography, so open that his greatest challenge was remaining discreet and not giving his subjects the chance to pose: The challenge was to find the moments when you weren’t noticed as a photographer, where you weren’t the subject of their attention […] Generally speaking I would say 99 per cent of people were open to photography and me being there, so that’s what was great about walking around Baku. I felt at home there among the people, even though I don’t speak the language, Russian or Azeri.

All the same Kollasch - who always shoots in black and white, loving the tones and contrasts and focus this gives the subjects - admitted that the language barrier affected how close he could get to the people: There’s only so far you can go with gestures and a few words and smiles and faith, he said.

Of the images in the book that stand out for him are the ethereal landscape of Icheri Sheher on the front cover (see p.67) and the picture of a woman with shopping bags appearing in the distance between two train cars: I went in there [the train yard- Ed.] and I wondered how long it would take for them to kick me out… it took 15 minutes, but I got that photo so I was really happy with it, Kollasch explained, laughing. The cops were really nice too, I have to say… they were very civil, but it was clear that I couldn’t stay.

A woman carries cleaning supplies between the wagons she cleans for this night train to Georgia. 2015

A woman carries cleaning supplies between the wagons she cleans for this night train to Georgia. 2015

An open door

So ultimately, I asked the authors, what is the book all about? For Kollasch: the book shows a vibrant, diverse life in Baku, of the everyday people, of their trying to get through life, through their games (nard) and family, commerce, enjoying each other, so I think the book is a statement of the everyday life of the common people of Baku.

Meanwhile Estoppey told me the following: Our book for me is a picture, we took a picture of Baku from 2013 to 2016. We took a picture and that picture is the book. And we don’t want to be judgemental about what we saw in Baku, we just want to emphasise and show and describe what we thought was strong, interesting, funny, not usual. We want to encourage people to go to Baku and actually see for themselves.

In such a way, as Estoppey notes in her concluding essay, Approaching Baku is like an “open door,” inviting each of us to step through and form our own individual opinions of the culture, people and landscapes we encounter in the words and images. Meanwhile for those of us foreigners living and working here and struggling to navigate the unfamiliar sights and sounds, it’s also a comforting reminder that we are just “Outsiders Looking In.”|

Approaching Baku: Outsiders Looking In // A l’approche de Bakou: Regards extérieurs About the authors: Anthea Estoppey is a Swiss journalist from Neuchâtel currently based in Cameroon. Matt Kollasch is an American photographer from Iowa currently living in Kosovo. To see more of his work, visit www.kollarfoto.com. |