When Ohioan Martha Lawry moved to Azerbaijan in 2010, rather than renting an apartment she chose to live with a host family and has remained with them ever since. Here she writes about her experiences of life in the district of Keshle, an unfamiliar area of Baku for most expats...

My first acquaintance with Keshle was at night as I peered out from a bus window, utterly lost. I wondered where on earth I was and why this foreboding tangle of dark alleyways didn’t look more like the rest of Baku. That was before I had a smartphone with GPS so I could track my descent into the abyss every time I was in the process of getting lost on an unfamiliar bus route, even if I couldn’t always prevent it.

Little did I know then that these very streets would become the place where I feel safest in the world

It was late winter of 2010. I had just arrived in the city to work on a master’s and was living with a host family in another part of town. I had stayed out late with friends in the city that night. They put me on a bus home, hoping I would recognize where to get off the bus even though I had never seen most of the territory along the way. I was feeling progressively less confident about that idea as the bus weaved on through endless back streets, the only ambient light shining out from the windows of smoky chaykhanas (cheap, mostly male-dominated tea shops) and bars full of tipsy moustachioed men. I shuddered to imagine a solo female traveller wandering into one of those establishments at night. Little did I know then that these very streets would become the place where I feel safest in the world (including my homeland in suburban America).

Local boys hitch a ride behind the number 38, which goes toward Ulduz metro station. Photo: Tom Marsden

Local boys hitch a ride behind the number 38, which goes toward Ulduz metro station. Photo: Tom Marsden

How in the world did you end up in Keshle? is among the first few questions most people ask when they meet me. Granted, it’s not a common tourist destination. Local colleagues dropping me off by car after work one night questioned my sanity for staying in such a “remote” place. There might be stray dogs out here, they said. Actually, there are some free-range neighbourhood dogs, but they quietly coexist with the settlement residents, and I like to think they are as accustomed as I am to the familiar faces washing in and out during the morning and evening pedestrian tides. They don’t even pose a threat to the chickens some residents set free to peck around in front of their gates.

The real danger is not the dogs; it’s whatever is tied up outside the butcher shop anxiously waiting to meet its fate the next morning. One dusky evening, I was daydreaming on my way home and nearly stumbled within kicking range of a cow at the edge of the road.

Many Keshle streets are narrow and have no sidewalks, so pedestrians and cars share space. Photo: Tom Marsden

Many Keshle streets are narrow and have no sidewalks, so pedestrians and cars share space. Photo: Tom Marsden

Aside from the urbanized farm animals, this neighbourhood is home to about 25,000 people. Locals claim that the settlement was populated at least as early as the 17th century, citing its historic mosque (more on that below), but the outskirts of the settlement developed much more recently. Many residents are first- or second-generation migrants from Azerbaijan’s rural areas. It is common for people moving into the city to cluster together with others from their regions as much as possible. The southeast side of Keshle, for example, hosts so many families from western Azerbaijan that when I asked one city taxi driver to take me there, he immediately said, Oh! Isn’t that where all the people from Gedebey live? He had no idea that’s exactly where my host family is from.

There’s something beautifully community-building about people slogging down the street like ducks in single file

Keshle is a residential zone known as a qesebe (settlement). This community is mostly made up of independent homes, each surrounded by a tall cinder block wall and metal gate. Some of the gates open into a heyat, or yard, containing two or three houses owned by one extended family. Don’t let the word “yard” mislead you, though: much of the ground in Keshle properties is covered with paver stones or cement.

The roads are also paved from wall to wall with no sidewalks, creating drainage challenges after rainstorms. One winter was particularly wet, and our street was submerged under no less than five centimetres of water for about a week. There’s something beautifully community-building about people slogging down the street like ducks in single file, watching where others have suddenly found their feet at surprising depths and trying to pick their way across on the highest ground.

In fact, it’s just this community atmosphere that draws me to Keshle. There are not many businesses or establishments significant enough to attract outside visitors, so residents feel safe from the invasion of riff-raff. When I first moved into the community in 2010, members of my local family walked me down the winding 10-minute route to the bus stop and met me there in the evenings to walk me home again for the first week. I kept insisting I knew the way on my own and there was no need to accompany me, but finally they explained that their real purpose was for the neighbours to see me with them. They wanted Keshle to know whom I belonged to.

Belonging here matters, or at least it used to. My host family tells a story about an incident about 35 years ago, when the east side of Keshle was still a Wild West and residents were more territorial. Anvar, then a university student, came to Keshle to visit his uncle who had recently moved in from Gedebey. Anvar got to the bus in the evening and was cut short by a group of young men demanding to know what business he had coming into their neighbourhood. He was not allowed to pass them until he dropped the appropriate names to convince them he was related to their neighbour and hadn’t come wandering in to chase local women.

Neighbourhood boys show off their wall, where sensitive residents have painted over a curse on anyone who dumps garbage in the street. Photo: Tom Marsden

Neighbourhood boys show off their wall, where sensitive residents have painted over a curse on anyone who dumps garbage in the street. Photo: Tom Marsden

That type of confrontation may not happen anymore, but the territorialism of Keshle lives on. The turning point that made me feel safer in this neighbourhood than anywhere else on earth occurred late one summer night while the darkness promised cooler temperatures but the day’s heat still radiated up off the pavement. Suddenly in the street a woman screamed.

My host brother, normally a heavy sleeper, leaped out of bed and pulled on pants as he ran outside. I sped to the window overlooking the street. I was amazed at how many gates opened almost simultaneously as men came out to investigate the noise. Within 30 seconds of the scream, there were 11 men surrounding the woman (and, as it turned out, the man she was arguing with). They demanded to know why anyone would disturb the peace in their neighbourhood and made sure the woman was safe.

I realized that the close proximity of houses to the road and the natural curiosity of residents meant I would have “strength in numbers” even when I was walking home alone through the dark streets. In Keshle, I was never outside hollering distance from at least a dozen potential cavaliers.

And cavaliers they are. On 4 September 2011, three residents were killed on the main road that passes Keshle (Babek Prospekti) when a driver failed to stop at a pedestrian crosswalk. The very next day, the neighbours called on a young journalist (himself a graduate of a Keshle high school) to bring a film crew. They formed a human chain across Babek and refused to let the resulting traffic jam clear up until they had secured footage of a phone call with an official who promised to install a traffic light within a week. The official followed through, and the residents now have a safer way to cross over to their bus stop.

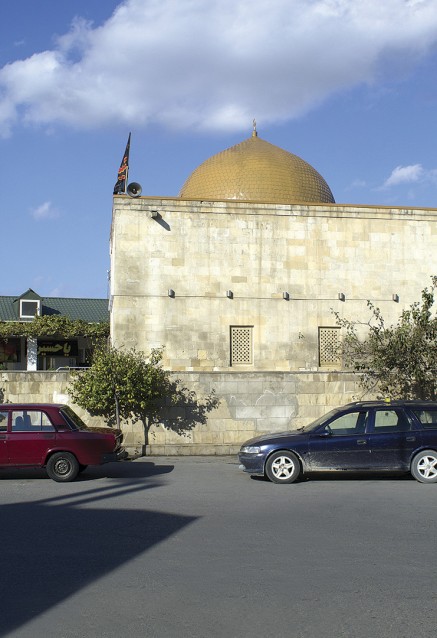

Another unifying element for the Keshle community is its mosque. According to the Azerbaijan State Committee for Work with Religious Organizations, the limestone building dates back to the late 17th century. It was commissioned by Shah Abbas II, a Safavid shah of Iran who expanded Persian influence in the Caucasus. During the Soviet period, the mosque was non-functional and used for storage, but it was reinstated to religious service in 1989. Locals note that the mosque is unique because its gate faces west, not east or towards qibla like most mosques. Mosque leaders claim this is because the eastern external wall of the building used to feature a shallow carving of a classic Persian sun and lion symbol which was only visible in the shadows of sunrise and sunset, but 300 years of wind and rain have eroded it into a blank wall.

Teymur, a neighbour, shows off his bicycle in front of his friend Ismet’s barbershop. Photo: Tom Marsden

Teymur, a neighbour, shows off his bicycle in front of his friend Ismet’s barbershop. Photo: Tom Marsden

Other parts of Keshle’s history are slowly being erased as well. During the Soviet period, it was home to the Baku Tobacco Factory, Keshle Machinery Factory and Baku Meat Combine, among other industries. These have all closed. But maybe that’s not all bad. The blank slate created by the closure of these big businesses has paved the way for smaller startups to paint a new future direction for the neighbourhood. For example, the Meat Combine property is still marked by a huge rusty gate bearing symbols of unfortunate cows, but now the gate permanently stands open, and the repurposed apartments inside are served by a cake shop and the youthful, grungy Baku Paintball Centre.

Maybe small businesses like these will someday put Keshle on the map. I would be personally grateful – the only complaint I have about life in Keshle is that Uber drivers can never seem to find their way through it!