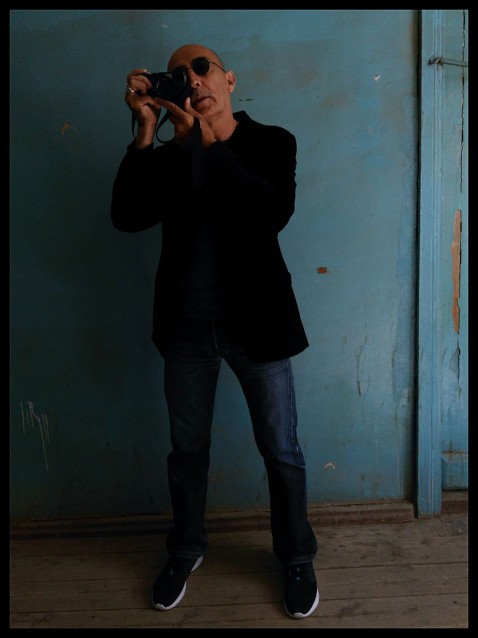

If you look at the “about” section of Sanan Aleskerov’s new website, it won’t take you long to understand that this is a man well versed in photography. In the world of smartphones where everyone’s a photographer, meeting Sanan is a breath of fresh air, because as digital technology moves photography into increasingly new territories, Sanan continues to find inspiration in photography’s classics.

We meet one afternoon in spring outside the former Admiral’s Park in Bayil, a district of Baku once home to Tsarist and Soviet naval bases. Today traces of history can still be seen: the park is surrounded by characterful old houses and Sanan himself lives in a former military barracks. We climb the old stairs, pass a mural depicting a sailor and arrive at the door of his workshop-cum-flat – spacious and minimalist, simple and stylish, but then what would you expect from one of Azerbaijan’s most respected photographers.

Black and white images of differing sizes decorate the lounge walls. One grabs my attention in particular – hanging to the right of the divan the large photograph shows a middle-aged man in a relaxed pose with an Olympus hung around his neck. Who’s this? I ask. That’s Josef Koudelka, Sanan says, referring to the legendary Magnum photographer who documented the Prague Spring in 1968. Koudelka is one of Sanan’s photographic idols, along with the likes of Eugene Smith and Edward Western, both of whom remain relevant despite the ever-changing nature of the image-making world. Eugene Smith lived the stories he wanted to tell, while Western appreciated very simple things, he tried to understand their inner essence, says Sanan, revealing something of his own practice.

For me photography is something I can’t be cured of, it’s forever…

Key to Sanan’s philosophy is the idea that Reality is beautiful the way you saw it, as opposed to the excessive editing common to the photography business today, even at prestigious competitions such as World Press Photo. This, warns Sanan, causes images to lose their natural documentary value: As you change it the life disappears, the truth disappears, half the strength is erased. It was this documentary nature of photography that for Sanan, despite the many artists in his family, distinguished it from other visual art forms and attracted him to the genre: I understood that photography is strong in the sense that it tells you the truth, you believe it more [than other visual art forms].

Czech photographer Koudelka was a true documentarian who embodied this approach; his name is a recurring theme throughout our conversation. Explaining the Magnum photographer’s influence on him, Sanan says: His book “Gypsies” showed me the 19th century, perhaps even the 18th century, happening in the 20th century. If you look at it you feel as though you’ve been transported to a different time.

Photography as a way of life

The photography business has changed much over recent years and Sanan believes there isn’t the demand for good documentary photography nowadays. Today he makes a living mainly through teaching, aside from shooting the occasional piece for publications like Baku magazine. But for Sanan, it’s never really been about making money; photography is sooner a practice, a way of life:

Everyone wants fame and money: yes, perhaps there will be, but perhaps there won’t, he says frankly. Rather, Sanan suggests that young photographers abide by a completely different principle: I love this and I’m going to do it, good or bad, important or unimportant, fashionable or unfashionable, it doesn’t matter, I’m doing what I love. That’s it.

Like Vivian Maier, I suggest, whose incredible photographic archives were remarkably found only following her death.

Vivian Maier – she’s a genius, Sanan says, because she had a childlike attitude towards photography. She said “I want to” and she did. She had a child-like gaze and didn’t seek any rewards whatsoever; she just loved [photography].

On the contrary he laments the fact that among the Azerbaijani photographers he admires – Eva Abilova, Ilkin Huseynov, Ramina Saadathana, Tahmina Ahmedova – the latter three haven’t fully given themselves over to the medium, practising only from time to time or giving up altogether to pursue other things because there isn’t the demand:

For me photography is something I can’t be cured of, it’s forever… I think that if God gave you a talent for something, you are responsible for that talent

What originally led me to Sanan was an interview I read with another Baku-born photographer, Rena Effendi, who is perhaps the only Azerbaijani photographer to really break into the global documentary photography market. Effendi turned up at Sanan’s workshop in the early 2000s a complete beginner armed only with a small point-and-shoot camera but quickly developed into a rising star. She knew what she wanted and went straight for it, Sanan tells me, yet much of her success must also be down to him:

I’m always telling my students that you have to be able to look properly, if you can do this then sometimes you don’t even need any teachers. It’s like a state of zen, a sort of yoga, when you look and begin to see.

This ability to examine, understand and go into a picture, according to Sanan, is a very rare gift. Often, at exhibitions for example, many approach a picture, simply look for a second and then move on. But photographers, he says, also need several other things: physical strength in order to walk (rather than drive) for mile after mile, the ability to talk to people, languages and contacts.

From documentary to art

Sanan’s own path into photography began during his compulsory military service in the Soviet army, or more precisely just prior to this when he stumbled across two issues of the magazine Czech Photo Review. This introduced him to the likes of Western, Josef Sudek, Duane Michaels, Ralph Gibson, Henri Cartier-Bresson (famous for his ‘decisive moment’ concept), all of whom continue to influence him today. He returned to civilian life in Baku with the conviction: I want to be a photographer, and although never receiving any formal photographic education, he studied at the journalism faculty of Baku State University and then worked in the photo lab of a research institute, taking any spare moment to go out and photograph.

Then came a shift in his practice. He began working for Azerinfo, the Azerbaijan branch of the Soviet news agency TASS, but left after only a year disappointed in the lack of genuine photojournalism:

It was all staged photography there, there wasn’t even reportage, everything was staged. I mean, you go to a factory, put people in place… “You look that way, you look at the book and you talk to him,” set the exposure and click. This was boring for me.

Sanan contrasts this with a reportage he did with a good reporter about the ecological situation in Sumgayit. It was perestroika and Moscow and TASS praised the work, but here, we were told, you’re disgracing Azerbaijan. So Sanan left TASS and moved away from news photography altogether.

A Russian journalist visiting Baku in the aftermath of Black January (20 January 1990), from the series "Alley of Shahids". Photo: Sanan Aleskerov

A Russian journalist visiting Baku in the aftermath of Black January (20 January 1990), from the series "Alley of Shahids". Photo: Sanan Aleskerov

The galleries on his website illustrate this shift. Only one is traditionally photojournalistic: in January 1990 he photographed the aftermath of Black January, when over 130 civilians were killed during a crackdown on Baku by Soviet troops. As we scan through the images on his desktop he lingers on one showing a Russian journalist seated at a table surrounded by local Azerbaijanis, pointing out their emotional, angry faces which contrast strikingly with the quiet teacup saucer and bread sitting on the table in front of the journalist. It was the journalist’s compatriots that were responsible for the tragedy, Sanan says, and so the Azerbaijanis had every right to be angry, yet the image subtly alludes to Baku’s respect for guests, regardless of circumstances.

Of more recent projects he shows me a more conceptual series on Baku’s old district of Sovietskiy, commissioned by Yarat in 2015. The images show little fragments of human life in a disappearing world – details on doors, marks on walls. It’s about my childhood memories, Sanan says, adding that he never lived in Sovietskiy but used to go often to visit friends. The one constant throughout the galleries is his preference for black and white, at times in the square form rendered by his old Rolleiflex, at others in the more traditional 4x5.

Looking back on the evolution of his style, Sanan explains: It’s always been boring for me to photograph the same things. So at first I photographed deserted streets, architecture. I didn’t photograph people because I didn’t trust them, I didn’t feel anything genuine in talking to them. Then I began to trust people more, began to photograph people and portraits, then I began to pay attention to the street and so on and so forth.

My interests change from time to time but that doesn’t mean that they disappear, the streets, portraits, architecture, the historical part, are all still there. I’ve added eternal things: rocks, trees, clouds, things that don’t change for thousands of years.

Bayil - still the Soviet Union

Today, rather than any concrete themes Sanan simply photographs his life: My camera is always on my shoulder, he says. He pays attention above all to the quality of light rather than shape or form and finds inspiration in good books, films or conversations with friends. One series, Ukhodyashie (lit. People walking away or leaving), has been underway for over 20 years and is inspired by passages in the Bible and Qur’an about people walking away from things that they disagree with. Central to his photography, however, is Baku, the city in which he has always lived:

I like the fact that Baku has this sort of hidden life which you have to work really hard to uncover - it’s a mystery, he says.

I ask to what extent Baku has changed over recent years. 100 per cent, he says, adding that Baku was always a multinational city in Soviet times and, like St Petersburg and Kazan, a centre of intellectual life. Since then many newcomers have arrived and brought with them their own language and culture. For example, he says, people often don’t understand why he keeps a dog at home; his neighbour particularly likes to challenge him on this.

Nevertheless Sanan still encounters little traces of the city’s past: Even though the city is changing very much, it’s growing, becoming more modern, clean, I still see lots of things connected to my childhood, that’s to say the 1950s and 60s…

Where? I ask, intrigued.

Bayil, he replies without a moment’s hesitation, It’s still the Soviet Union!

Perhaps this affection for his native city explains why, unlike Effendi and countless other photographers, Sanan has never taken his photography skills abroad. More broadly, he says, this is a matter of interests: Sanan’s lie more in psychology, art and exploring his inner self and for this you don’t need to go anywhere, as opposed to more traditional photojournalism. However, he admits that finally, at 60 years of age, the desire to travel and live abroad, to see something different, has recently emerged.

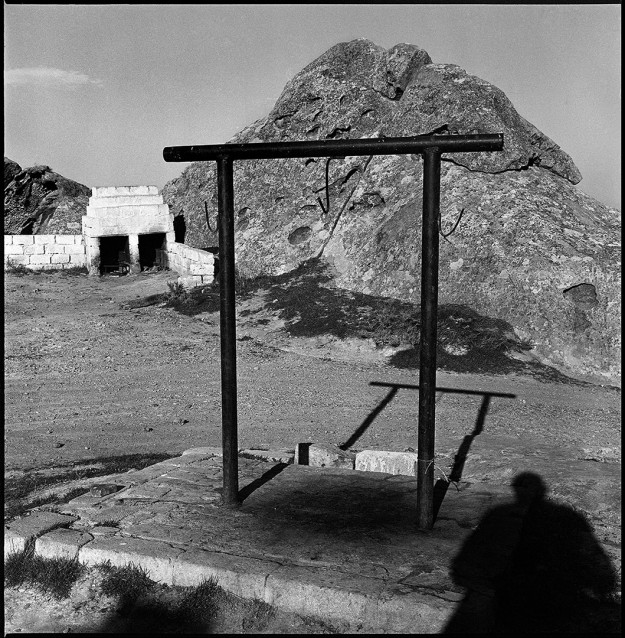

But, curiously, this doesn’t necessarily mean taking pictures. Whereas in Baku, as he says, When I go to Qobustan I know what I’ll photograph; I know all the rocks, I know where what type of tree grows, Sanan fears that without living somewhere for an extended period of time his pictures will barely scratch the surface. For example, Koudelka came to Baku twice: the first time to photograph (see the series on Sanan’s website) and the second to show Sanan samples of his work, yet they both agreed that the Magnum legend hadn’t shot anything interesting:

You have to live here, to see here, walk, watch, speak, because for example the Shirvanshah’s Palace is very small but so interesting, you have to study it, Sanan says.

Photographing the obvious isn’t among Sanan’s interests. Rather, he says: I’m interested in going to see how people live, interested in going to a rich person and a poor person, to an artist and a guy that works in the sewers. I’m interested in these people but you need a lot of time for this.

Such a commitment to time is generally a daunting prospect but if there’s anything I have learnt from my brief conversation with Sanan, it’s the idea of photography as a practice, demanding patience and perseverance, dedication and love. Forget the fame, lofty ideals, money and awards and simply do what it is that you love. This seems to be the essence of life through the lens of Sanan Aleskerov.